Friends,

I don’t know the full story. We never do.

Until a few years ago, I was a willing subscriber to a family myth. The myth, which I repeated in my first book From Rice to Riches, was that my Scottish great-grandfather married my Chinese great grandmother in colonial China around 1880. It sounded promising. East meets West. A cultural blend which gave me inroads into an identity story about being a connector and a bridge-builder. As a journalist, I felt it gave me an early ability to see both sides of a story. Hah.

It was a lie.

The arrival of my seafaring Scottish ancestors to China and Hong Kong in the late Nineteenth Century, certainly added some wayward branches to the family tree. My maternal great grandfather Alexander Ryrie Greaves was one of tens of thousands of working-class Britons lured to China with the enticement of earning better money and making a name for themselves before leaving the Far East. Alexander or Alec as he was called, was born in Liverpool, but identified himself as Scottish.

Alec’s grandmother had brought the family from the Hebridean Island of Stornoway (Scotland) in 1829 to Liverpool (England). Her husband, a lieutenant in the Royal Navy had just died. So she took her children on a schooner and joined her brother in the thriving port city. Young Alec was born in Liverpool a year after an uncle, a sea captain whom he was named after, was lost at sea on a clipper ship travelling between Shanghai and Hong Kong.

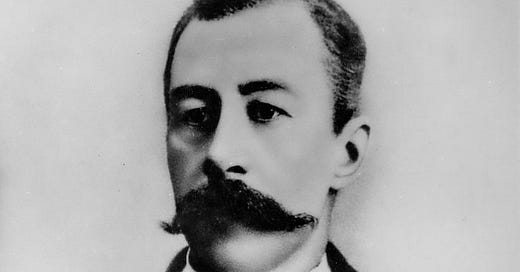

Alec worked for several companies in the colonial treaty ports of Mainland China and resided in Hankow and Shanghai. Here he is as a young man.

At some stage, he met a Chinese woman who came from the southern province of Canton (Guangdong). We don’t know much about who she was, what she did for a living or the type of person she was. It’s likely Alec gave her the English name, Josephine. There is no record of how they met or how they described their union or conducted their relationship. They had five children together, two of whom died either in utero or after birth. The first surviving child, Winifred, was born in 1882. Alfred followed two years later. My grandfather, Keat, was born in 1887. From several verbal accounts, the Greaves family lived together in a house. We have a photo of young Josephine with the three Greaves children. They are mixed-race of course, known in those days as Eurasian.

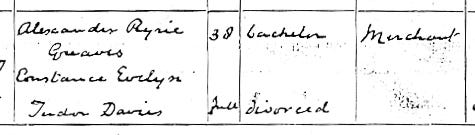

By the early 1890’s Alec and Josephine’s relationship was over. Josephine took the children to Hong Kong where she raised them on her own. Alec, it seems, didn’t plan to leave China as a single man. In 1894 when he was thirty-eight years old, he married an English divorcee in Shanghai. Her name was Constance. Their marriage certificate described Alec as a bachelor.

I am not sure if this is bigamy either now or back in its time. From my family’s understanding, Alec never had anything to do with his former de-facto Chinese partner. Nor did he have anything to do with his children. No details of any paternity arrangements have been uncovered. His will does not mention them. The records don’t tell the full story about my tree; the Chinese branch of the Greaves family.

I’ve often imagined writing a TV drama where the lead character (me) gets to go back to 1880’s China to find out exactly how Alexander and Josephine lived and what was said when he abandoned her (or perhaps she walked out?). In Hong Kong there were laws aimed at protecting the mistresses of colonial subjects. Not the case in Shanghai. In my imaginary TV drama (inspiration from a series called Lost in Austen, 2008) my character, confronts Alec and demands he accounts for his behaviour.

Continuing this fantasy, I wonder, what would I say if I found myself in the presence of my great grandfather? As a journalist, I would interview him, of course. Here’s some of the questions I’d ask:

Did anyone in your (British) family know of your relationship with Josephine?

Why didn’t you make provision for your children in your will?

Did you think about the three children you abandoned as you got older? What sorts of things did you think about?

Did you feel an iota of discomfort about your relationship status with Josephine?

What would you say to Josephine now?

What would you say to your three children now?

Are you ashamed of your behaviour (although it was probably considered the default at the time)?

Did you have other mistresses and are there other Greaves we don’t know about?

Were you a serial bigamist (if that’s the correct word to use)?

Did you die in peace?

The world of family history is full of stories like mine. People who get to do the work we do are usually white and privileged. We spend our money and years of our lives searching for information about the past. Do we search hard enough for the truth? Or are we content to accept as indigenous academic Victoria Grieves Williams suggests “the myth of great white men and women, bravely opening new worlds and taming the wilderness.”

There is fascinating work underway to examine critical family history. That is, the truth beyond superficial readings of our ancestors existence, their pretty diaries and touching photos. Pastor and genealogist Diane Kenaston has put together an entire research guide on Genealogy and Racism: A Guide for White People.

Our ancestors were works in progress, just as we are. They, like us, sometimes participated in oppressive systems and sometimes resisted them. [We need to] engage this complex legacy. - Diane Kenaston, pastor and genealogist

Here in Australia I’ve been deeply moved by the work of journalist David Marr. In 2023 he published Killing for Country an investigation into his ancestors role in murdering scores of indigenous people during the land grabs that preceded the creation of Australia. This truth-telling, as it’s known in Australia, is the necessary work of good family historians.

My investigations into my own family are far from over. I am lucky to have other truth-tellers in my living family tree. Am I way off the mark with my own truth-telling? Maybe. But in the spirit of sharing, shouldn’t we all be a bit more vulnerable, a bit less certain and open to learning another side to our stories?

You said :) -' But in the spirit of sharing, shouldn’t we all be a bit more vulnerable, a bit less certain and open to learning another side to our stories?'

Exactly Jane I believe it's the only way to closing Any Gap

What was the first version of the story you thought was true? How did you come to find out the truth? I think that would make an interesting story in itself. I write about how I discover things and what changes from what I thought was true.